Being a 160m fullwave horizontal loop at 65 feet, used on all bands from 160 to 6 meters.

Those Trees, though!

Nearing retirement in 2018 I decided to dust off my ham ticket and get back on the air after being off the air for over 25 years. During that time I had moved my family to Ohio because of a job opportunity. Our house is in the middle of about about 4 acres of very tall hardwood trees. So the first challenge was to figure out how to launch ropes over 70 foot high branches in the woods. But that is the subject of another post.

The second challenge was figuring out what to hang on those ropes to cover as many bands as possible. Out came the boxes of old antenna books I had accumulated over the years. Even while inactive, I did keep up with QST and QEX so I was aware of advances in the technology. One thing that had improved was the design of high quailty, low loss baluns that could cover the HF spectrum and work under high SWR.

Some things old become new again, it seems. With new balun technology and the availability of autotuners, older multiband antenna designs became more practical than ever.

Some Good Choices

There are a number of good choices for a multi-band antenna on a single feedline.

- Off Center Fed dipoles (OCF)

- Doublets,

- End fed wires

- Trap Dipoles

- Fan Dipoles

- Verticals

- Loops

The first three are very similar. They are all a single wire a half wavelength or so long on their lowest frequency of usage. They differ in where the feedpoint is located along the single wire.

The Horizontal Patterns

When planning an antenna system, the most important thing when it comes to performance is their horizontal and vertical patterns. Where is your RF going?

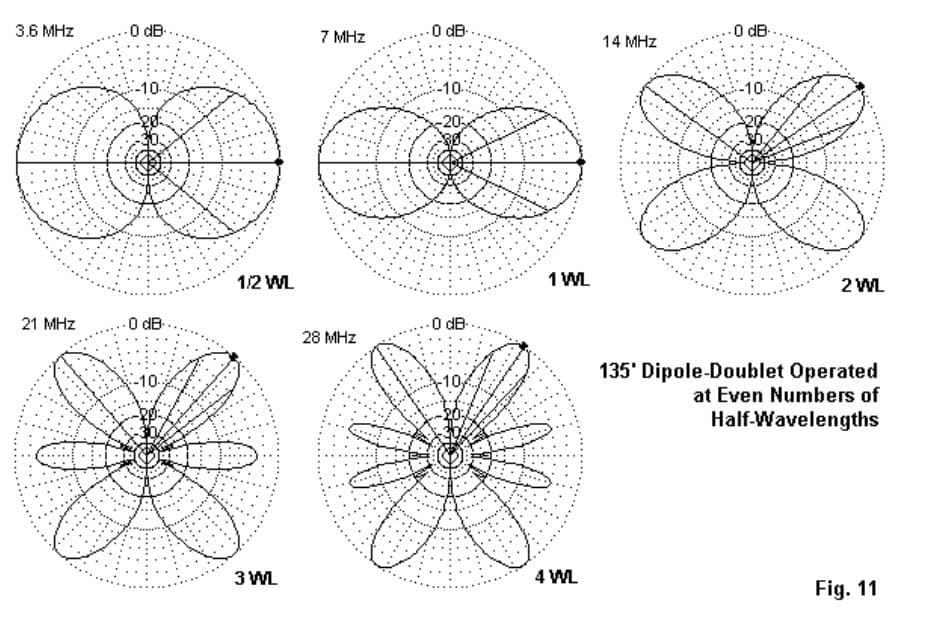

The first three choices on the list all have pretty much the same pattern both vertically and horizontally. Since the vertical pattern is the same for almost all of the choices on the list, it pays to consider the horizontal pattern. The figure below is a cross section of the horizontal pattern looking down on the antenna wire. If the wire runs north to south, the figures below represent a compass dial with north at the top. As you can see, the pattern is a figure-8 on the lowest band, breaking up into ever more lobes and nulls like a cloverleaf as you move up the bands.

The Fan Dipole and the Trap Dipole end up looking like a half wave dipole on each band, so their patterns are a broad figure-8 on all the bands. Their pattern on each band would all be like the first one in the upper-left in the figure above.

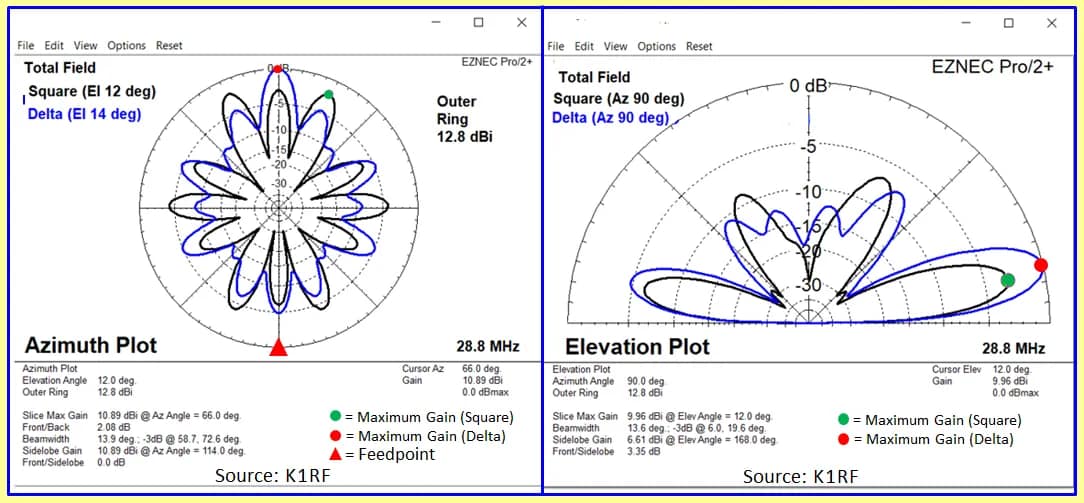

The Loop is not a single linear piece of wire. So its pattern is different than the ones discussed above. It is virtually omni-directional on its lowest wavelength of usage, and the pattern does “cloverleaf” like the single wires on the higher bands, but the lobes and nulls are distributed around the compass more evenly than the single wires. The figure below shows an 80 meter fullwave loop on 10 meters,

Common Mode RF

Common moder RF is when RF ends up on the feedline because of a number of imbalances in the antenna design. When there is common mode RF, the feedline becomes part of the radiating structure which throws off the pattern. It also has the potential for bringing RF into the shack.

Conversely, the same problem effects the receiving performance as well. The patterns for transmitting and receiving are the same. A bigger problem is when the feedline is part of the receiving structure and it comes into the shack near all the noisy electrical wiring.

The fan dipole, the doublet, and the loop are all symmetrically fed in the center so they have the potential for much less common mode RF on the feedline. Whereas the end-fed design might be the worst offender in that regard, the OCF can still be troublesome without special care and feeding.

The Horizontal Loop stands out in regard to common mode RF. A Loop that is a full wavelength long on its lowest band is highly resistant to common mode RF on all that band and all the harmonic bands.

The vertical antenna is a whole ‘nother thing. I will post a separate article on the tradeoffs and advantages of horizontal vs vertical antennas.

Practical Considerations

Finally, there are the practical considerations. I has trees and a lot of ropes and wire. The fan dipole and the trap dipole are a construction project of their own. Whereas, the doublet, OCF, loop, and End-Fed are a single piece of wire.

All those considerations brought me down to either a multi-band doublet or a multiband Skyloop. A doublet is a good choice because of its simplicity.

Given all the space and trees, I opted for the Skyloop because it is more omni-directional and it is very immune to common mode problems on the feedline and rumor has it that loops are quieter (more on that below). The Skyloop is the same configuration as the doublet shown above, but the antenna wire is a full wavelength long and forms a horizontal loop.

One final consideration made it attractive, which is unlike the doublet, the impedances on the lowest band and all the harmonically related bands stay within a few hundred ohms. While some feed the loop directly with coax, I opted to use 300 ohm twinlead that comes down to a hefty 4:1 balun on a fencepost near the edge of the woods on which is also mounted a remote autotuner. That leaves all the SWR on the twinlead and the balun. The tuner providing a clean match to the buried coax run to the shack.

You will see a lot of articles for Skyloops using 450 ohm feedline. That is not a bad choice, but I chose 300 ohm feedline on the advice of W8JI, who pointed out that the feedpoint impedance of the loop on the harmonic bands are all within a few hundred ohms.

The Tuning Results

By the time I trimmed the loop a few times, I ended up with a match so close that the autotuner hardly does any work except on the non-harmonic WARC bands. Here is the RigExpert analyzer plot taken on the coax side of the 4:1 balun with no tuner inline.

One might think the 4:1 balun is an obvious choice given the 300 to 50 ohm transformation that is required, but that is not quite accurate. The impedance at the balun end of the feedline will be a function of the feedpoint impedance, the band in question, and the length of the feedline. This is because any length of feedline is a kind of impedance transformer. What is present at one end is not necessarily what is present at the other end, except when the one end is at the characteristic impedance of the feedline.

So what I was going to see at the balun end of the feedline would be somewhat arbitrary with my 60 feet or so of feedline. But it so happens it turned out just fine as seen by the plot above. In case you missed it, I would like to point out something that you will find with most single wire multiband antenna designs. Note that the lowest SWR down at 160m band is below the band, whereas, the sweet spot for the harmonic bands fall right within each band.

The reason for this is stray capacitance that causes the wire to seem electrically slightly shorter at higher frequencies. So one has to trim the wire slightly longer to get things to fall in line on as many bands as possible. It is a very small price to pay, though, given that losses on the feedline due to SWR are lowest on the lowest band, and, in this case, the twinlead is already low loss in the face of any SWR compared to coax.

The Installation

Here is the fencepost with balun, autotuner, and a polyphasor bonding the coax to a ground rod before it runs underground to the shack:

The short white pvc pipe serves as a strain relief for when the feedline is whipped around from wind, or from the support trees blowing around.

There is over 520 feet of wire in air forming a rounghly rectangular loop held up at four corners by support ropes. The wire goes over a few tree canopies with no problem as those trees blow around in the wind. The average height of the loop is about 65 feet.

The wire is #14 copper coated stranded steel with a strong hard abrasion resistant insulation. The wire is strong enough that at times I had my full weight on it horsing it from being hung up on stubborn branches. If it fails someday, it will be a failure of branches, ropes, or pulleys, in my opinion.

On The Air

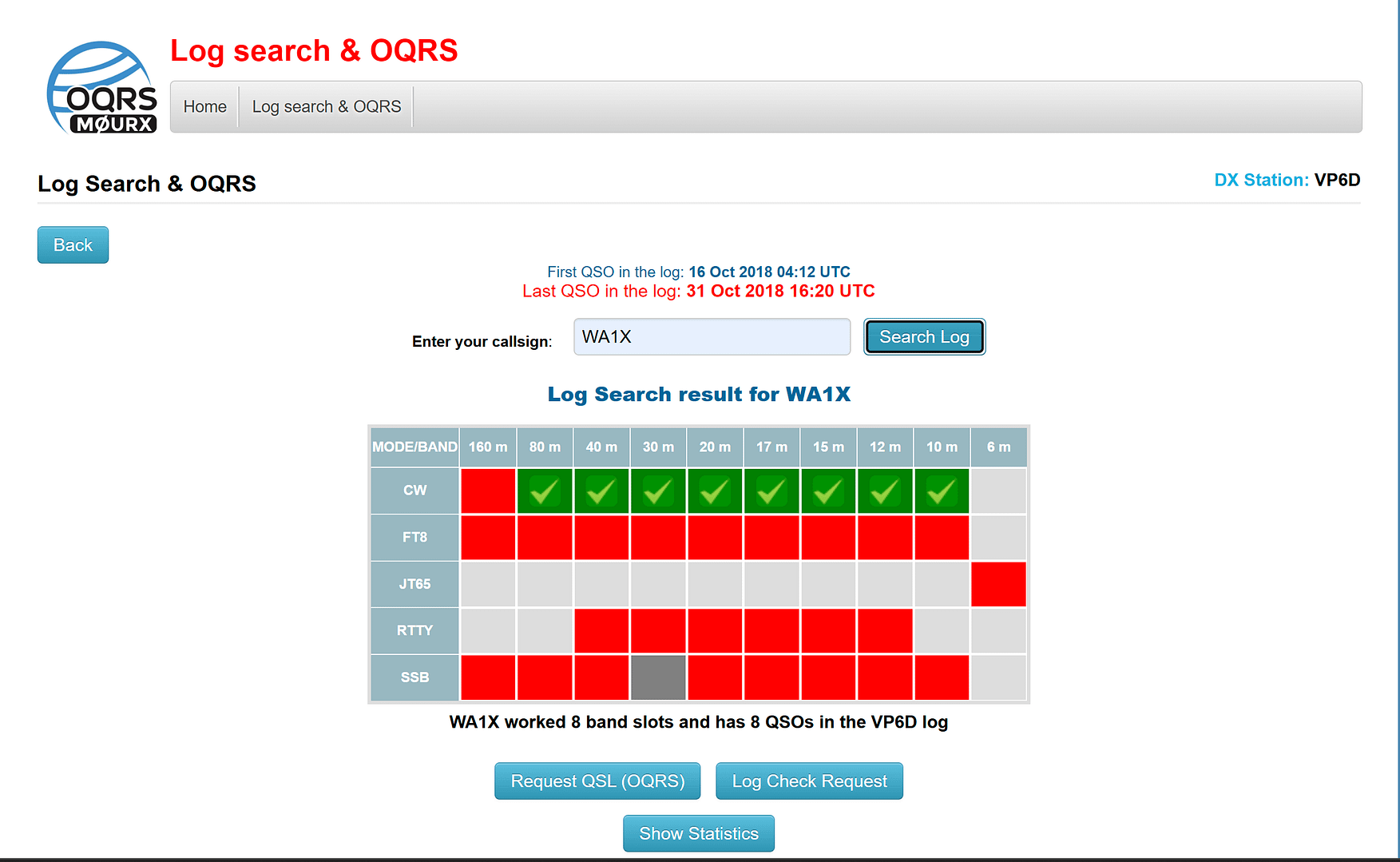

The results have been excellent. Soon after I put it up my first opportunity to really break it in was the Ducie Island DXpedition in the fall of that year. I manage to work them on all bands from 160 meters to 10 meters. And we were not yet in the peak of the sunspot cycle.

Yes, I know it doesn’t show a 160m contact, but I did work them. I believe they mislogged my callsign. Honest. I caught them on the early one morning as the greyline was moving out across the Pacific Ocean. The crazier thing was working them one evening on 10m in 2018 at the low ebb of sunspot cycle before Cycle 25.

In the first few years of usage I racked up about 210 DXCC countries with 100 watts CW. Since then I am now up to 245 DXCC countries. This includes a few contacts on 6 meters during a brief opening.

All I can say is that it works very well. I crack pileups and do well in contests. The other thing I can say is that the installation has been rock solid for almost 7 years now, including the operation of the remove autotuner. It has survived all kinds of bad weather here in NE Ohio, and keeps on ticking.

Is It Quiet?

The Loop is dead quiet. Naturally, on the lower bands the signal to noise is established by atmospherics at the very least. On the upper bands, it is very quiet. Any band above 20m where the signal to noise is a result of nearby electrical noise and your own receiver, when those bands our out, the antenna is like a ghost.

Are loops inherently quiet? I can’t tell you since this is the only antenna I have used at this QTH. I live in rural Ohio on a cul-de-sac, in the middle of the woods. All the utilities in my neighborhood come through underground. So I have an ideal situation. One thing I can say is that my personal theory is that a lot of electrical noise one hears on one’s ham antenna may be due to common mode pickup on the coax. In this loop installation, everything is condusive to suppressing common mode RF on the coax.